- Home

- Koomson, Dorothy

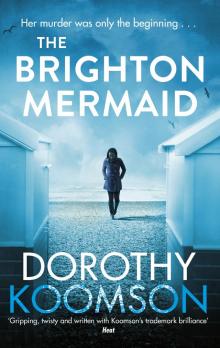

The Brighton Mermaid

The Brighton Mermaid Read online

Contents

About the Book

About the Author

Title Page

Dedication

Acknowledgements

Prologue

1993

Nell

Now

Nell

1993

Nell

Now

Macy

Nell

Macy

Nell

1993

Nell

Now

Nell

Macy

Nell

Macy

1993

Nell

Now

Nell

1993

Nell

Now

Nell

1993

Nell

Now

Macy

Nell

Now

Nell

1993

Nell

1994

Nell

Now

Macy

Nell

2007

Nell

Now

Nell

1994

Nell

Now

Nell

2000

Nell

Now

Macy

Nell

Macy

Nell

2007

Nell

Now

Nell

Macy

Nell

Macy

Nell

2013

Nell

2015

Nell

Now

Nell

Macy

Nell

Macy

Nell

Macy

Nell

Nell

Nell

Nell

Nell

Nell

Macy

Nell

Macy

Nell

Nell

Nell

Nell

Macy

Nell

Macy

Nell

Macy

Macy

Nell

Nell

Nell

Nell

Macy

Nell

Nell

Macy

Nell

Nell

Macy

Nell

Macy

Nell

Macy

1993

Nell

Now

Nell

Macy

Nell

Nell

Macy

Nell

1993

Jude

Now

Nell

Nell

Macy

Copyright

About the Book

Brighton Beach, 1993

Teenagers Nell and Jude find the body of a young woman and when no one comes to claim her, she becomes known as the Brighton Mermaid. Nell is still struggling to move on when, three weeks later, Jude disappears.

Twenty-five years on, Nell is forced to quit her job to find out who the Brighton Mermaid really was – and what happened to her best friend that summer.

But as Nell edges closer to the truth, dangerous things start to happen. Someone seems to be watching her every move, and soon she starts to wonder who in her life she can actually trust …

Fast-paced and thrilling, The Brighton Mermaid explores the deadly secrets of those closest to you.

About the Author

Dorothy Koomson is the award-winning author of 14 novels including more than 12 Sunday Times bestsellers. Her books have been translated into more than 30 languages and she continues to be a method writer whenever possible. She wrote The Brighton Mermaid in part as a love letter to the place she’s called home for more than ten years. And she hopes you enjoy it.

Dorothy Koomson in order: The Cupid Effect, The Chocolate Run, My Best Friend’s Girl, Marshmallows for Breakfast, Goodnight, Beautiful, The Ice Cream Girls, The Woman He Loved Before, The Rose Petal Beach, The Flavours of Love, That Girl From Nowhere, When I Was Invisible, The Friend, The Beach Wedding, The Brighton Mermaid .

To those who are missing and those who love them.

Acknowledgements

Hurrah! I get to say thank you to all these wonderful people …

The ones who help make this book happen: Ant and James; Susan, Cass, Hattie, Charlotte, Rebecca, Emily, Aslan, Jason, Emma, Becky and everyone else at my publishers; Emma D.

To the ones who help to keep me going: my lovely family and friends, G, E & M.

To the ones who buy the book: You.

And a special thank you to Graham, for the police advice .

Prologue

Saturday, 2 June

The ground is uneven and crunchy underfoot, and I stumble when I hit it. But it takes a microsecond to steady myself, to force myself upright and then to start running.

I make it off the gravel driveway, through the gap in the hedge and then out into the fields that surround the farmhouse. In this inky blackness, in the distance, I can just about make out shapes – bushes, hedges, a line of trees far, far down over the fields. I need to get to the trees. If I can get to the trees, I can hide.

Thud, thud, thud, thud! The world around me is full of their footsteps, moving across the earth, chasing me down.

My legs are stiff from where I’ve been lying in the same position for so long, and they protest as I try to pick up the pace, attempt to run faster over the uneven, soggy ground.

Thud, thud, thud, thud! The noise … the vibrations … They sound horribly closer now.

Thud, thud, thud, thud! There’s a fire in my chest where my lungs should be, and my eyes are struggling in the darkness as it constantly changes the shape of the horizon. But I can’t stop, I can’t even slow down, I have to keep moving.

Thud, thud, thud, thud! Nearer and nearer.

Thud, thud, thud, thud! I need my legs to go faster. I need them to call up the muscle memory of when I used to do this, when I had to literally run for my life. I can do this. I have to do this. I have to reach the trees. I’ll be safe there, I’ll be able to hide there.

Thud, thud, thud, thud! fills my ears. Thud, thud, thud, thud! They’re right behind me. Thud, thud, thud, thud! My ragged breathing, the whistle of the wind, the creak of my bones are all drowned out by it. Thud, thud, thud, thud!

I have to go faster. I have to—

1993

Nell

Saturday, 26 June

‘Maybe she’s asleep,’ I said to my best friend, Jude.

We were both staring at her. She looked so soft, lying there on top of the pebbles, half in, half out of the water, her face serene. Even with the foamy tide constantly nudging at her, trying to get her to wake up, she was still; tranquil, lifeless.

‘She’s not asleep,’ Jude said. Her voice was stern, angry almost, as though she couldn’t believe I was being so stupid.

‘I know she’s not asleep,’ I replied. ‘But if I pretend she’s asleep then she’s not the other thing.’ I couldn’t bear for her to be the other thing and for me to be standing there in front of her when she was the other thing.

‘She’s not asleep,’ Jude repeated, gentler this time. ‘She’s … she’s not asleep.’

We both stood and stared.

From the promenade, I’d spotted her down on the beach, the light of the almost full moon shining down on her, and said we should check to see if she was all right. Jude had wanted us to keep going, getting back to her house after we’d sneaked out was going to be tricky enough without getting back even later than 3 a.m., which was the time no

w. But I’d insisted we check. What if she’d twisted her ankle and couldn’t get up? How would we feel, leaving someone who was hurt alone like that? What if she’s drunk and has fallen asleep on the beach when the tide was out and is now too drunk to wake up and pull herself out of the water? How would we live with ourselves if we read in the paper in the morning that she’d been washed out to sea and had drowned?

Jude had rolled her eyes at me, had reminded me in an angry whisper that even though our mums were at work (they were both nurses on night duty), her dad was at home asleep and could wake up any minute now to find us gone. He’d call my dad and then we’d be for it. She’d grumbled this while going towards the stone steps that led to the beach. She was all talk, was Jude – she wouldn’t want to leave someone who was hurt, she would want to help as much as I did. It wasn’t until we’d got nearer, close enough to be able to count the breaths that weren’t going in and out of her chest, that we could to see what the real situation was. And I said that thing about her being asleep.

‘I’ll go up to the … I’ll go and call the police,’ Jude said. She didn’t even give me a chance to say I would do it before she was gone – crunching the pebbles underfoot as she tried to get away as fast as possible.

Alone, I felt foolish and scared at the same time. This wasn’t meant to turn out this way. We were meant to come to the beach and help a drunk lady and then sneak back to Jude’s house. I wasn’t supposed to be standing next to someone who was asleep but not.

She must be cold , I thought suddenly. Her vest top was soaked through and stuck to her body like a second, clingy skin; her denim skirt, which didn’t quite reach down to her knees, was also wringing wet. ‘I wish I had a blanket that I could pull over you ,’ I silently said to her. ‘If I had a blanket, I’d do my best to keep you warm .’

It was summer, but not that warm. I wasn’t sure why she was only wearing a vest, skirt and no shoes. Maybe , I thought, her shoes and jumper have already been washed out to sea .

I leant forwards to have another look at her. I wanted to make her feel more comfortable, to move her head from resting on her left arm at an awkward angle, and stop her face from being pushed into the dozens and dozens of bracelets she wore on her arm. Thin metal ones, bright plastic ones, wood ones, black rubbery ones, they stretched from her wrist to her elbow, some of them not visible because of where her head rested. I wanted to gently move her head off her arm and lay it instead on my rolled-up jacket. I didn’t dare touch her though. I didn’t dare move any nearer, let alone touch her.

Her other arm, the right one, was thrown out to one side, as if it had flopped there when she’d finally fallen asleep. That arm had only one slender silver charm bracelet, hung with lots of little silver figures. That arm’s real decoration, though, was an elegant and detailed tattoo of a mermaid. My eyes wouldn’t leave the tattoo, which was so clear in the moonlight. Usually when I saw tattoos they were a faded greeny-blue, etched into peach or white skin, but this one was on a girl with the same shade skin as me. Deep black ink had artistically been used to stain and adorn most of her inner forearm. I leant a little more forwards, not wanting to get too close, but fascinated enough to want to have a better look. It was truly beautiful, so incredibly detailed it looked like it had been carefully inscribed onto paper, not rendered on skin.

I could see every curl of the mermaid’s short, black Afro hair; I could make out the tiny squares of light in her pupils; I could count every one of the individually etched scales on her tail, and I could see droplets of water glistening on the bodice, shaped of green seaweed, that covered her torso. The mermaid sat on a craggy grey rock, her hands demurely crossed in her lap, smiling at anyone who cared to look at her.

I couldn’t stop staring at her. She was mythical, she was a picture, but she was also like a siren at whom I couldn’t stop staring. In the waters beneath the mermaid’s rock, there were three words in a swirling, watery script: ‘I am Brighton’.

Now

Nell

Friday, 23 March

‘And I’m sure you will all join me in wishing Nell good luck with her next venture,’ says Mr Whitby, manager of the London Road branch of The Super supermarket chain. I have worked with him there, latterly as his assistant manager, for nearly eight years. Eight years. I hadn’t intended staying that long but somehow I never got around to leaving until today. I’ve finally saved up enough to take twelve months off paid employment, and, hopefully, at the end of it, I’ll have solved the mystery that has haunted me for nearly twenty-five years. Hopefully, at the end of it, I will be able to walk away with my family still in one piece.

We’re in Read My Lips, one of those ‘hot’ new bars that seem to pop up every few months in Brighton. It’s a short walk from the Pier and we’re in our own cordoned-off VIP area downstairs with brightly coloured squashy seats and mirrored tables. The lighting is the darker side of ‘muted’ and the music is the wannabe side of grime. And it is packed. Ordinarily there would be no way for us to get in here, but Mr W, who suggested we come here for my leaving do, said he had ‘connections’ that would get us in. The twenty of us who’ve come out tonight have been impressed so far. Even more so when he insisted on buying the drinks – completely out of character for a man who usually leaves dealing with customers and staff to his assistant manager. (He seems to have issues with not letting his true feelings – not caring – come through.)

In the slightly brighter corner that we’ve been allocated, Mr W peers at me over his wire-rimmed glasses. ‘I think it’s fair to say that ever since we welcomed Nell into our Super family many, many years ago, we have nurtured and cared for her. We have overseen and, may I suggest, been fundamental in helping her to grow up into the vibrant young woman she is today. Obviously we are all a little sad and disappointed that Nell has chosen to leave us in the run-up to Easter, one of our busiest times, but we can forgive her. That is the nature of the family we have created here at The Super. And it is also the nature of our Super family to be willing, when Nell comes to her senses and realises where her future truly lies, to let her know that there will always be space on the clocking-in board for her.’

I stare at him, shocked. The other people who have come to celebrate with me stare at him, shocked. Not only has he spoken many, many words without doing his usual of breaking eye contact or allowing his tone to reveal how dull he is finding speaking to you, he has delivered a masterful example of passive-aggressiveness. I’m shocked that he has it in him.

The music in the bar could have been designed to accompany his speech – in the gap that follows his words the music crescendos, dramatically underlining what he’s said. It then drops away again as Mr Whitby raises his glass. ‘To Nell,’ he says happily.

Part of the assistant manager’s job at The Super was to let people know it was perfectly normal to feel unsettled and slightly anxious when they dealt with Mr W, so I pull a smile across my face, to tell everyone that despite what he said, it’s OK to raise their glasses too. ‘To Nell,’ my former colleagues chorus before they sip their drinks. I love these people, they make me smile. We at the London Road The Super are oddballs, there’s no pretending we’re not, but I adore them and I’m touched so many of them have come out tonight, especially when most of them have to be up early tomorrow to work a full shift. I’ll miss them.

‘In all the leaving speeches in all the years, I have never heard one like that ,’ Janice murmurs to me when everyone breaks off into smaller groups. She has worked at The Super longer than almost everyone here except Mr W. ‘I mean, that was the equivalent to him throwing himself at your ankles to stop you leaving.’ She smirks. ‘He’s going to miss you.’

‘You mean he’s going to miss the person who’s been assigned his quota of unused words?’

Janice smirks some more. Even I know I talk too much.

‘When I first resigned, he didn’t say a word. Not one word. I had to repeat it because I didn’t think he’d heard me and I thought that if h

e was going to break his usual silence it would be then. But no, he stored it all up for tonight. To tell me I’ve dropped you all in it with Easter and “mark my words, you’ll be back”.’ I shake my head. ‘Anyway, I need something to wash away the lingering taste of passive aggressiveness. Want something?’

Janice raises her nearly full flute of prosecco. I turn to the others. ‘Anyone want a drink?’ I ask above the music. As a group, they look at me as though I’m crazy – until Mr W stops supplying the drinks, no one is reaching into their pockets. ‘Fine,’ I say. ‘When you talk about this night in weeks to come, though, just remember that I offered, OK? Nell offered to buy drinks even though she isn’t going off to another paying job.’

The bar itself is lit up like a multicoloured beacon in the dark space but not many people are waiting to be served. I rest my bag on a padded stool and reach in for my purse.

By the time I stepped out of the Super building for the last time ever tonight, I was Nell again. As soon as I clocked off my final shift I shed my assistant manager persona and donned my usual T-shirt-and-red-jeans look, slotted in my various earrings, and pushed on my bangles, which go from forearm to wrist on my right arm and all the way up to my elbow on the left. Once I took my mobile off its waistband holster and slipped it into my jacket pocket, that was it. I was me again.

Once I am me again, of course, the messages start again.

Despite the music, the thrum of conversations around me, I hear the bleep-bleep-ting of a message tone from my mobile.

His tone.

It goes off in my pocket, but echoes in my chest.

Don’t read it , I tell myself even as I’m reaching for it. It can wait till morning , I remind myself as I pull my mobile out of my pocket. It’ll ruin your night , I state as I bring up the message.

I know before looking what it’s going to say, but I still have to take a deep breath before I look. It says the same thing every time – it uses the same five words to control me. Sometimes I think I look in the hope it will be different, that the screen after that message tone will say something else. But no, it’s the same as always:

He needs to see you.

The same five words as always, the same full stop as always. The same lack of greeting or sign-off. He needs to see you. He needs to see you . It bounces on the edges of the music, thumps on the beats of my heart. He needs to see you. He needs to see you. He needs to see you .

The Brighton Mermaid

The Brighton Mermaid